Catheter ablation has been used to treat heart rhythm disorders for more than 20 years. This therapy has evolved as one of the main strategies to treat atrial fibrillation (AFib). A long, thin tube called a catheter is inserted into the blood vessels, typically in the groin, and guided through the bloodstream into the heart.

When the tip of the catheter is placed against the part of the heart causing the arrhythmia, radiofrequency electrical current is applied through the catheter to produce a small burn about 6 to 8 mm in diameter to eliminate the arrhythmia focus.

Carto 3 System and SmartTouch Catheter

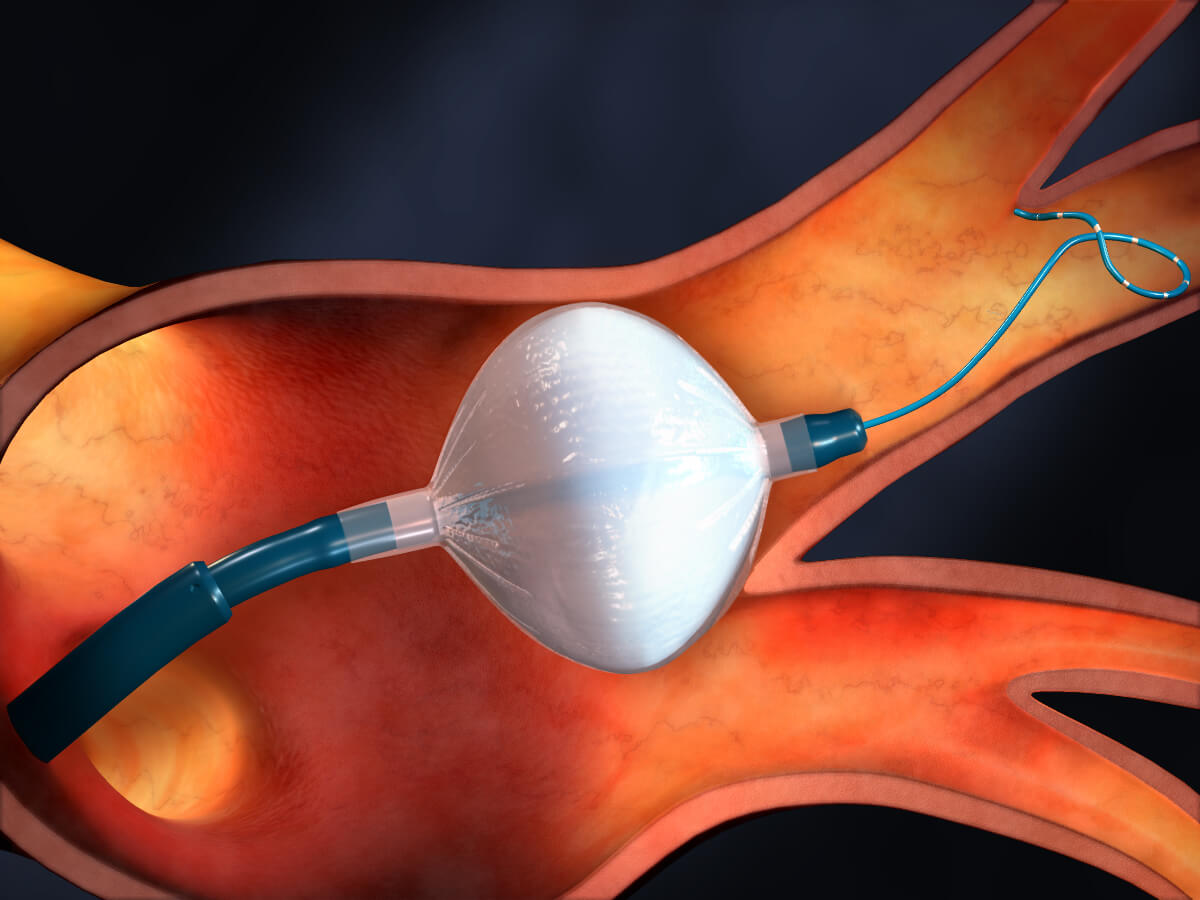

Another type of ablation uses a freezing balloon (Cryoballoon) catheter. Catheter ablation is very effective when the abnormal area is small, but in AFib, there are many electrical waves throughout the atria. AFib is often “triggered” by rapid electrical activity originating from small areas typically located around the pulmonary veins that drain blood from the lungs back to the left atrium. Initial studies showed that ablation of the triggers prevented AF in some patients. Subsequently, it was recognized that many triggering sites usually are present, leading to approaches in which the ablation catheter is used to place lesions that encircle multiple pulmonary veins regions to electrically isolate all of the potential triggers around the veins, as well as the electrical “substrate” that allows the AFib to sustain itself. With further study, it has become clear that the electrical abnormalities that promote AFib can be different for different people and that some people require more ablation lesions than others. The exact nature of the ablation procedure performed varies among patients.

Arctic Front Advance Cryoballoon Placed in Left Superior Pulmonary Vein, Courtesy of Medtronic

The procedure is success in maintaining sinus rhythm depends on the type of AFib and the severity of underlying disease. The success rate is low for patients who have had AFib continuously for many years (persistent AFib) with serious underlying heart disease. Success rates are high in patients who have intermittent episodes of AF (paroxysmal AFib) without other heart disease. In some patients, ablation does not completely prevent AFib but improves symptoms by reducing the frequency and severity of episodes or by making drug treatment more effective.

The risk of a major, life-threatening complication such as stroke or puncture of the heart with bleeding that can require surgery is approximately 1% to 2%. Rarely, ablation may damage the esophagus, which is located behind the left atrium, leading to fatal bleeding or stroke several days or weeks after the procedure. Damage to the phrenic nerve can paralyze the diaphragm, causing shortness of breath. Severe narrowing (stenosis) of the pulmonary veins, is very uncommon with current ablation strategies, but it can impede blood flow from the lungs to the heart and can cause shortness of breath, cough, and pneumonia.